My love affair with making mix-tapes

Reproduction of an article from Nialler9.

Growing up in 1980s Ireland, one of the most desired forms of legal tender that a music-mad kid might wish for was to be in possession of a cluster of blank cassette tapes. Having blank tapes was a huge first step to being able to listen to a song loved, any time that suited you, instead of being dependent on hoping a DJ might spin it while you happened to be listening to the radio.

There was an economy of delay back then that’s almost impossible to fathom in the internet era, where everything is available immediately and on-demand. Now, when someone mentions a track or artist to you, within moments you can go online and immerse yourself in their sound (and every word, image and opinion ascribed to said artist).

Pocket money back then was spent on sweets and comics, but I used to put some money aside in order to buy batches of blank cassettes, which were available in hardware stores, electrical shops and some record stores.

With a blank tape, you had the opportunity to copy your favourite record – if you could get a hold of it (!) – and possess a replica for yourself, which you could listen to anytime you pleased, be it on your Walkman, your ‘double'-deck,” or perhaps in the car … if your parents’ car should have a cassette player.

In eighties Ireland, you might first read about a song in a magazine such as Smash Hits, or grasp a careless whisper of a tune on pop radio (RTÉ Radio 2, or Radio Luxembourg), or even on TV ( Top Of The Pops or on Vincent Hanley’s MT USA show). Then – unless you happened to be quick enough on the draw to have recorded the song from the source at that very moment in time – if you wanted to hear it again, you either had to wait until another DJ happened to play the same song on another show, or you had to try and find someone who had actually bought the album and make a recording. There was a certain thrill associated with the slow, patient hunt for a track that contemporary music lovers no longer get to experience.

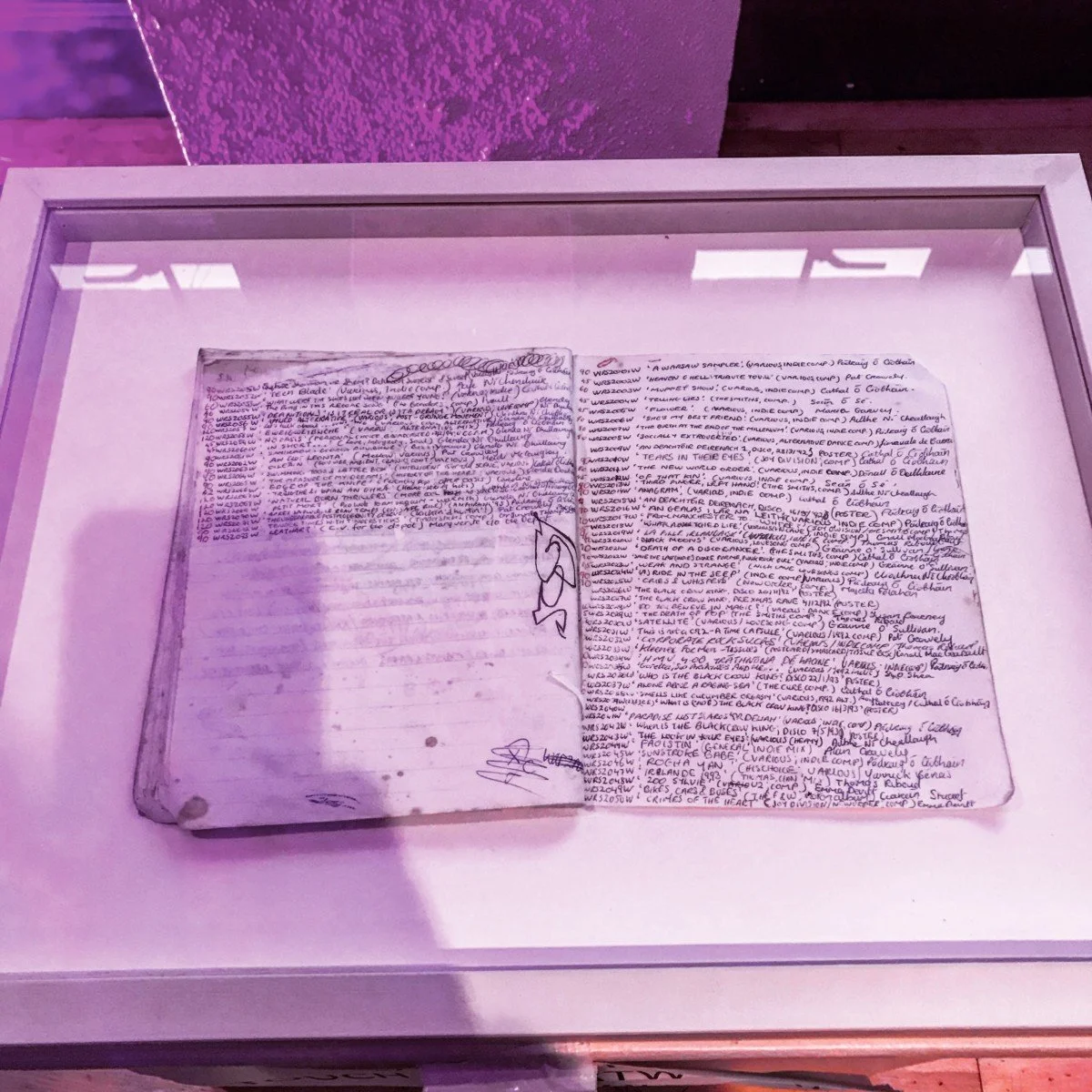

I kept a record of every mix-tape I made in this copybook

Blank tapes cost a fraction of a cassette album so it made sense to find someone who actually had bought the album, so that you could borrow it from them, then copy it. You could pretty much pick up ten 90 minute blank cassettes (C90s) for the price of brand new album. Each C90 might reasonably house two whole albums, so that was 20 albums for the price of one! No wonder the music industry was aghast that ‘home recording is killing music’ as thousands of pint-sized pirates built up an arsenal of copied music, where the artist never received a penny. Very innocent times, when you consider the prevalence of free music files online now.

It was companies such as BBC, BASF, Bush, Mitsubishi, TDK, Sony and Maxwell who made these blank cassettes and benefited from the home recording industry. They manufactured blank cassettes of various duration. You had C60s (30 minutes each side), the more popular C90s (45 minutes each side) or – latterly – C120s (though these would often end up in a messy tangle due to to the excess amount of tape).

Provided you had the correct set-up, be it a “double-deck” which you could use to record one cassette to another, or a record player with a cassette recorder attached, you had the means to copy your friends’ records, your brother’s compilations or your aunt’s albums. While the recording took place (in real time), you might occupy the time by trying to mimic the font of the artwork as you transcribed the information to your blank tape covers. The more artistic kids might go the whole hog and ‘trace’ the entire album sleeve.

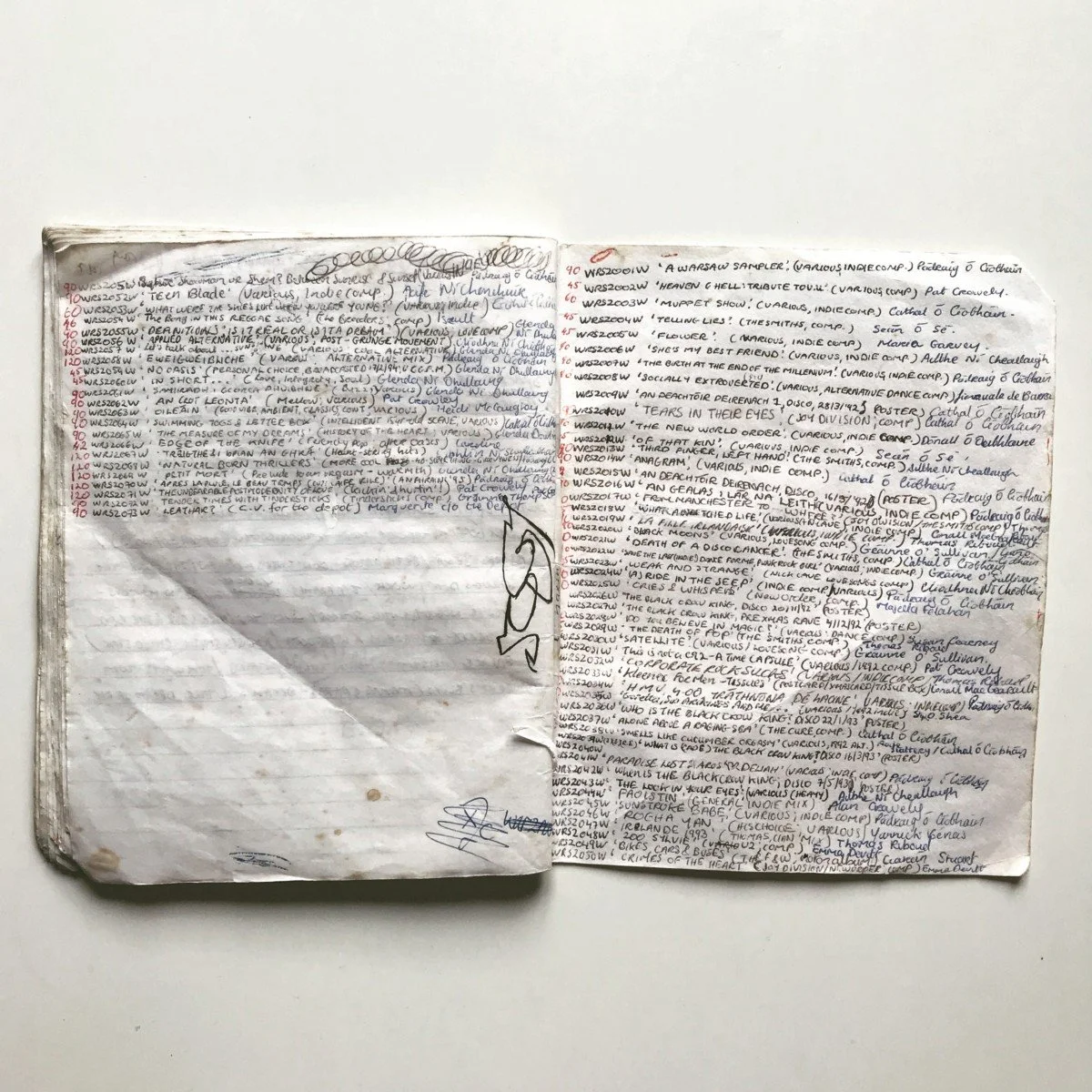

A list of every 90s mix-tape I made, accompanied with WRSZ catalogue number!

As boys and girls became teenagers, our musical horizons expanded beyond what was on mainstream pop radio.

In early 90s west Kerry, a culture emerged of discovering hitherto hard-to-find music and sharing it with our friends. There we are on the school bus, driving around Ceann Sléibhe en route to our respective schools (buachaillí agus cailiní, the boys to the CBS, the girls to the convent) in An Daingean on a cold January morning, exchanging albums by The Stone Roses, Cocteau Twins, Joy Division, The Go-Betweens and The Cure.

The back of the bus hummed with excitement as tapes were passed on from boy to girl, from girl to boy – for one night only, mind – so that we could bring the cassette home and record the contents with our blank tapes.

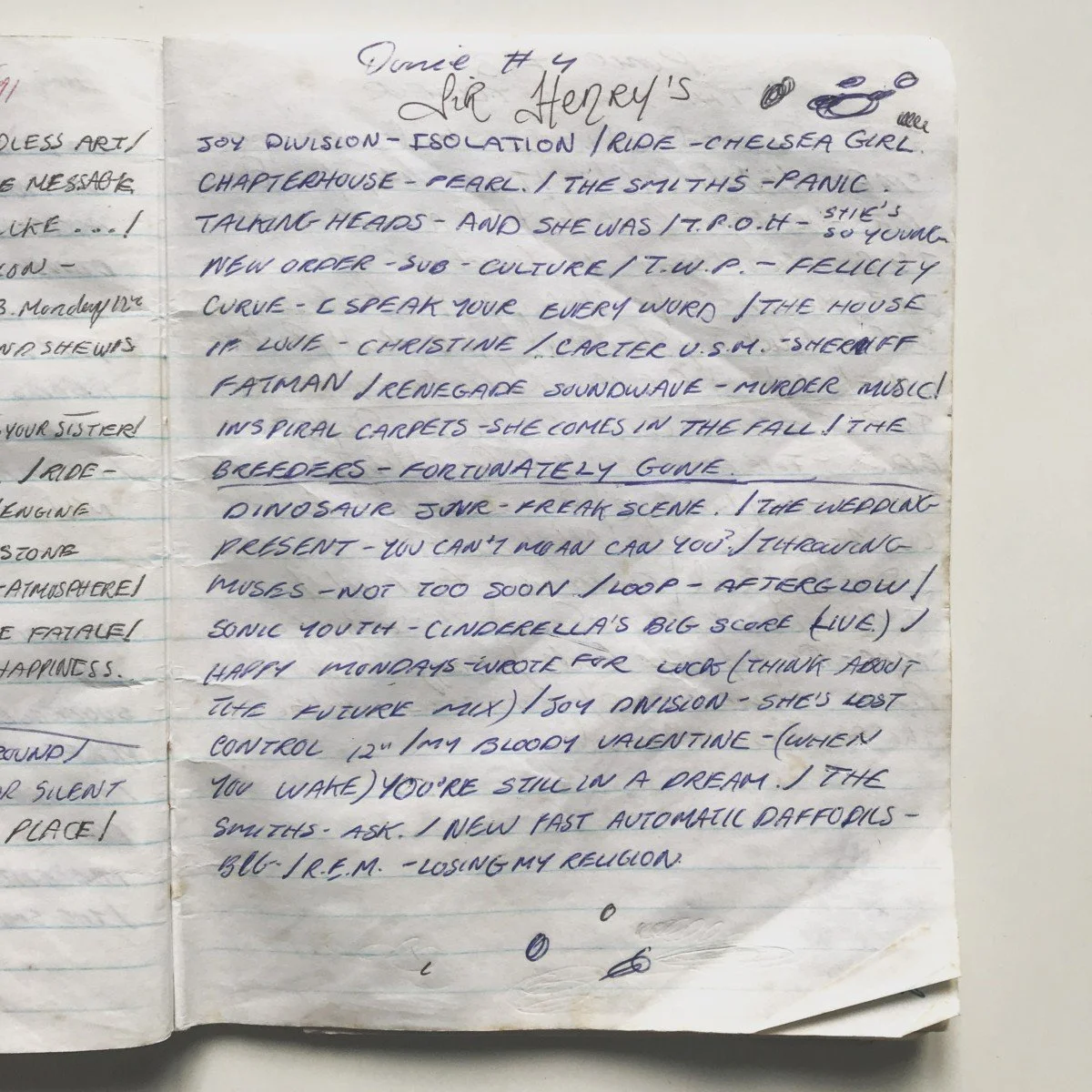

Soon we began to make cassette compilations for one another. I made countless mix-tapes, such was my evangelical zeal to share the music that I discovered. There might be a theme, such as ‘An Introduction to the Pixies’, or a more sublimated theme, such as ‘Listen to these songs and please like me, cos I think you’re beautiful’, or simply ‘Listen to these songs and I hope they fill you with as much wonder and joy as they fill me’.

Making a mix-tape took time. You had to choose the tracks that you wanted to include, then line up each individual track choice, one by one, from the various primary source cassettes, before hitting play and record (simultaneously!) on the blank cassette side of your “double-deck” (I still have the muscle memory of these manoeuvres). You would then remain close by until the song ended, so as to immediately press pause, then swiftly line up your next choice. We all became experts on finding that perfect song under 2 or 3 minutes that might fill up the last few seconds of one side of a blank tape. It was considered a type of sacrilege for a song to abruptly stop before the end of the tape, so you had to choose carefully. ‘Ana’ by Pixies, ‘Please Please Please Let Me Get What I Want’ by The Smiths or 'The High Monkey Monk’ by Cocteau Twins used to see out a lot of my mix-tapes.

Compilation I made for a friend - called Sir Henry’s, probably because I was obsessed with the iconic Cork venue, as recorded in my copybook

Because I was obsessed with Factory Records, I had my own imaginary bedroom/boutique record label called Warsaw Records (Warsaw being an early name for Joy Division). Each compilation I made had a WRSZ number attached to it, in the same way as Factory had a FACT number. Once I bestowed a cassette on someone, I rarely saw it again, but I did keep a catalogue, in which I listed all the compilations I made. This included the title of the compilation, the catalogue (WRSZ) number, for whom it was made for and all the tracks contained on the compilation (in case I’d make another tape for that person down the line and I wanted to ensure I wouldn’t be repeating myself).

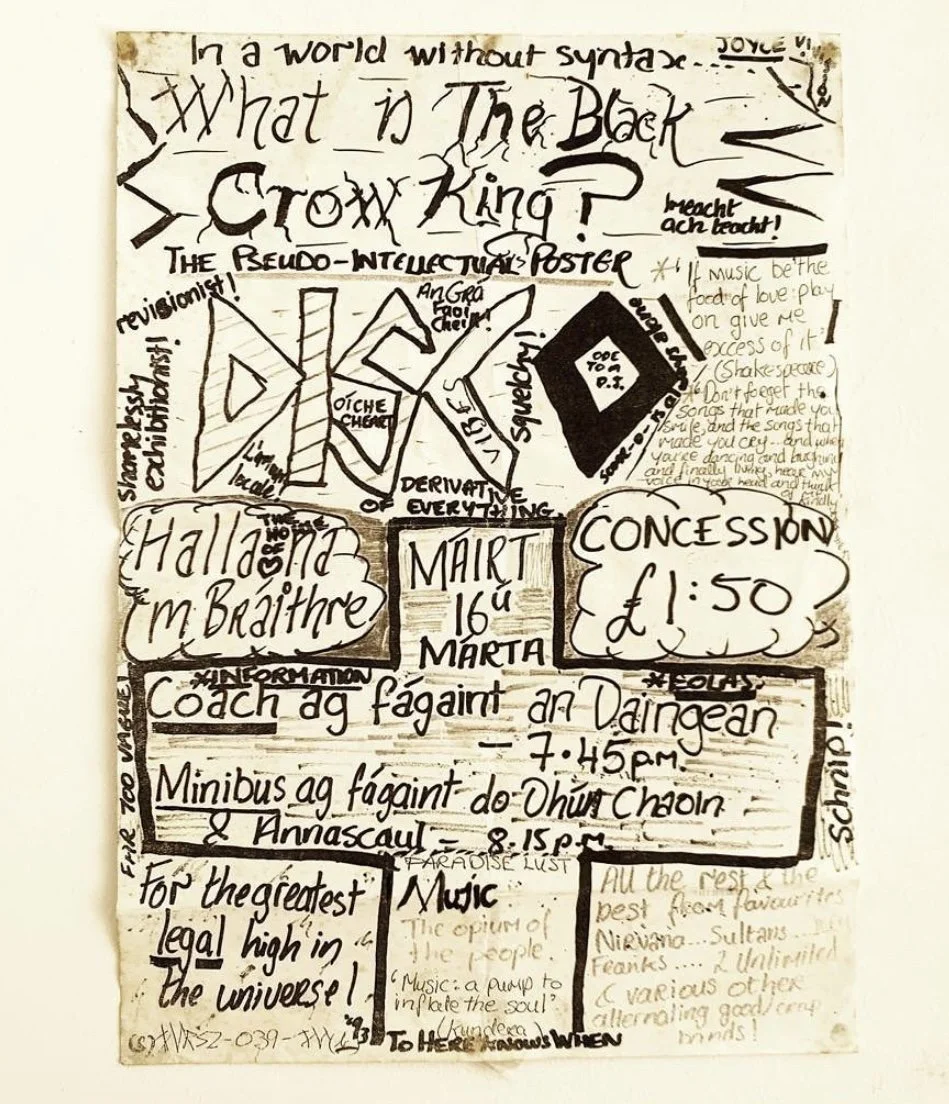

When I first began DJing at school and youth club discos around Dingle in the early 90s, I used to play my music off cassettes. CDs hadn’t yet taken off and I didn’t have much music on vinyl. Most of my music collection at that time was pretty much on cassette. I used to play tunes that were popular with my fellow teens, but also try and sneak in the odd indie track that I was really into. My DJ moniker at my first gigs was The Black Crow King (after a Nick Cave track).

Poster I made for a school disco I DJ’ed at, An Daingean, early 90’s

In many ways, this endeavour of finding music and sharing it with others is a blueprint for what I’ve been doing since 1999 on An Taobh Tuathail. The formats may have changed, but the idea remains the same. I spent my daylight hours immersed in and discovering music. Then when the red light signals to go on air each night, my radio show, becomes a mix-tape of sorts, full of wonderful sounds to be shared with you.

Said copybook was part of the ‘Waxing Lyrical’ exhibition of artwork on cassette culture at Other Voices in Dingle in 2017. I overheard one guy exclaim “Jesus, it’s like it’s The Koran or something”